METODOLOGÍA Y ANÁLISIS EN LA DIGITALIZACIóN DE CUERPOS MICROSCóPICOS: SU APLICACIóN A LOS ESTUDIOS FITOLÍTICOS

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.5710/PEAPA.25.08.2023.475Palabras clave:

Fitolitos 3D, Modelado, Esculpir, Dust3D, BlenderResumen

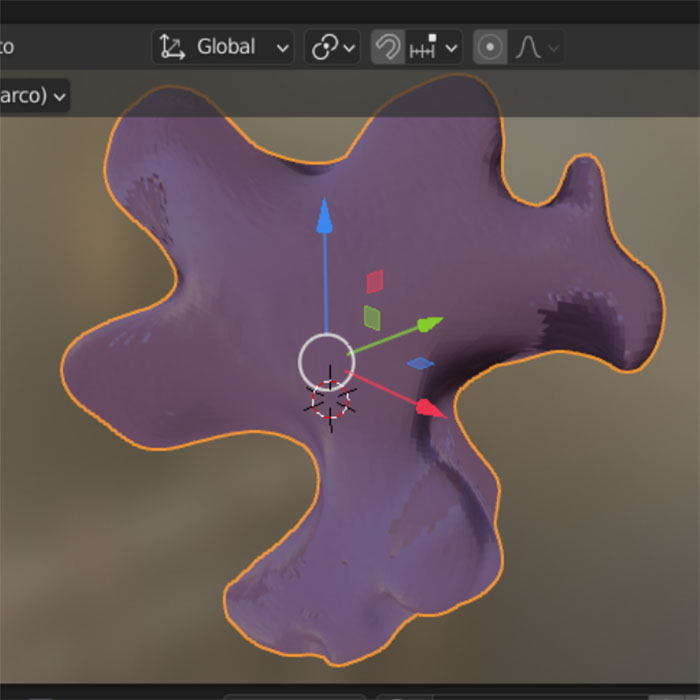

La continua evolución de herramientas aplicadas en digitalización y modelado 3D, en el último tiempo, ha permitido su utilidad en diferentes campos científicos, uno de ellos la paleontología, dando beneficios en relación al estudio y la exposición de materiales fósiles. En el presente trabajo se exponen dos metodologías para digitalización de morfotipos fitolíticos como modelos tridimensionales a partir de imágenes en dos dimensiones utilizando software de libre acceso, denominados modelo de burbujas y modo esculpir. Ambas metodologías se consideran complementarias a la hora de generar un modelo de fitolito tridimensional. Esta propuesta resulta eficaz para lograr modelados 3D, generando no sólo una forma amigable para visualizar dichos morfotipos, sino también una manera efectiva para el conocimiento y entendimiento de la variedad de morfologías que pueden caracterizar a los silicofitolitos.

Referencias

Alexandre, A., Basile-Doelsch, I., Delhaye, T., Borshneck, D. y Mazur, J. C., Reyerson, P. (2015). New Highlights of Phytolith Structure and Occluded Carbon Location: 3-D X-Ray Microscopy and NanoSIMS Results. Biogeosciences, 12, 863–873.

Autodesk, INC. (2019). Maya. Available from https:/ autodesk.com/maya.

Babot, M. P., Musaubach, M. G. y Gonzalez, J. A. (2016). Continuo morfológico y fitolitos 3D. Aportes desde una perspectiva arqueobotánica para definir conjuntos fitolíticos. En Zucol, A. F., Patterer, N.I., Colobig, M.M. y E. Moya (eds.). Taller de Micropaleoetnobotánica. Relevancia de una Red Interdisciplinaria de Investigaciones en Fitolitos y Almidones, Libro de Resúmenes, 79.

Bernardini, F. y Rushmeier, H. (2002). The 3D Model Acquisition Pipeline, 21, 149–172.

Blackman, E. (1971). Opaline silica in the range grasses of southern Alberta. Canadian Journal of Botany, 49, 769–781.

Boyde, A. (2004). Improved depth of field in the scanning electron microscope derived from through-focus image stacks. Scanning, 26, 265–269.

Brecko, J., Mathys, A., Dekoninck, W., Leponce, M., VandenSpiegel, D., Semal, P. (2014). Focus stacking: Comparing commercial top-end set-ups with a semi-automatic low budget approach. A possible solution for mass digitization of type specimens. ZooKeys, 464, 1–23.

Cignoni, P., Callieri, M., Corsini, M., Dellepiane, M., Ganovelli, F. y Ranzuglia, G. (2008). meshlab: an open-source mesh processing tool. 6th Eurographics Italian chapter conference, 129-136.

Davies, A. (2010). Close-up and macro photography (pp. 172). Focal Press, Elsevier, Oxford.

Domínguez-Quintana L., Rodríguez-Florido M. A., Ruiz-Alzola J. y Sosa D. (2004). Modelado 3D de Escenarios Virtuales Realistas para Simuladores Quirúrgicos Aplicados a la Funduplicatura de Nissen. Revista Informática y Salud, 1579–8070.

Ellis, R.P. (1979). A procedure for standardizing comparative leaf anatomy in the Poaceae. The leaf-blade as viewed in transverse section. Bothalia, 12, 65–109.

Erdtman, G. (1969). “Handbook of Palynology. An introduction to the study of pollen grains and spores”. Munksgaard (pp. 486). Copenhagen.

Gallaher, J. T., Akbar, S. Z., Klahs, P. C., Marvet, C. R., Senske, A. M., Clark, L. G. y Strömberg, C. A. E. (2020). 3D shape analysis of grass silica short cell phytoliths: a new method for fossil classification and analysis of shape evolution. New Phytologist, 228, 376–392.

Gallo, A., Muzzupappa, M. y Bruno, F. (2014). 3D reconstruction of small sized objects from a sequence of multi-focused images. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 15(2), 173–182.

Goldsmith, N. T. (2000). Deep focus; a digital image processing technique to produce improved focal depth in light microscopy. Image Analysis & Stereology, 19, 163–167.

Hess, R. (2010). Blender Foundations: The Essential Guide to Learning Blender 2.6. Focal Press.

Lanza, D. (2015). El uso de software libre en la teoría y práctica artística. Blender como plataforma digital para la creación escultórica. PIMCD Nro. 155. Universidad Complutense. Madrid.

McNeel, R y asociados. (2010). Rhinoceros 3D, Version 6.0. Robert McNeel & Associates, Seattle, WA.

Metcalfe, C. (1960). Anatomy of the Monocotyledons. 1. Gramineae. Clarendon Press. (pp. 731). Oxford.

Neumann, K., Strömberg, C. A. E., Ball, T., Albert, R. M., Vrydagh, L. y Scott Cumming, L. (2019). International code for phytolith nomenclature (ICPN) 2.0. Annals of Botany. Oxford, 20, 1–11.

Payne, A. (2011). Rapidform XOR3 Interface Basics. CAST Technical Publications Series. Number 5963.

Photomodeler Pro. (1997). User Manual. Eos Systems. Vancouver, Canada.

Piperno, D. R. (1988). Phytolith analysis: an archaeological and geological perspective, San Diego. pp. 280. Academic Press.

Piperno, D. R. (2006). Phytolith. A comprehensive guide for archaeologist and paleoecologist. 238 pp. Altamira Press

Radu, R. B y Cousins, S. (2011). "3D is here: Point Cloud Library (PCL)". IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 1–4.

Rovner, I. (1971). "Potential of Opal Phytoliths for use in Paleoecological Reconstruction", Quaternary Research, 9(3), 343–359.

Ruiz Torres, D. (2017). El uso de tecnologías digitales en la conservación, análisis y difusión del patrimonio cultural. En: Acción Cultural Española (AC/E). Anuario AC/E de Cultura Digital. 1ed.Madrid: Acción Cultural Española (AC/E), 1, 129–227.

Sederberg, T. W., Zheng, J., Bakenov, A., Nasri, A. (2003). T-splines and T-NURCCSs, ACM Trans. Graph, 22(3), 477–484.

Tindall, A. y Kalms, B. (2012). Guidance: Photographing specimens in natural history collections. Atlas of Living. Australia.

Tomlinson, P. B. (1961). Anatomy of the Monocotyledons. 2. Palmae. Oxford University Press. (pp. 453).

Archivos adicionales

Publicado

Número

Sección

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2023 Sebastián Ariel Frezzia, Alejandro Fabián Zucol

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-SinDerivadas 4.0.

Los/las autores/as conservan los derechos de autor/a y garantizan a la revista el derecho de ser la primera publicación del trabajo licenciado bajo una licencia CC Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 que permite a otros/as compartir el trabajo con el reconocimiento de la autoría y de la publicación inicial en esta revista.